We’re Excited to Participate in the 2019 LifeSpin Christmas Program!

December 13, 2019Important Client Updates Re: Coronavirus

March 15, 2020What’s changing when it comes to Divorce in Canada this July?

Note that due to COVID-19, the Government of Canada has announced that implementing these changes has been delayed until March 2021.

On June 21, 2019, changes to the federal Divorce Act contained in Bill C-78 were given Royal Assent, meaning they have become law, but the changes are not yet in effect. On July 1, 2020 the changes will come into force, and family law cases involving most married and divorced couples in Ontario and across Canada will unfold under the changed law.

If you were never married to the parent of your children, the provincial Family Law Act, Children’s Law Reform Act, and other statutes will continue to govern to your situation if your case is being litigated in Ontario. The Divorce Act also does not apply to common law spouses.

The first thing you may want to know if you’re already in the midst of a family court case, or if you already have a family court order involving custody, access, and parenting issues is what, if anything, will change for you. You may be asking “do I need to go back to family court?” once the changes to the Divorce Act come in to effect. The answer is that you can continue to rely on your existing order even after the law changes. You don’t have to come back to court automatically on July 1 just because of these changes.

Of course, if you choose to come back because you want to make changes to the parenting arrangements in your family, or if your ex files a motion to change your final order, then the changed law will apply to your case if an order is made after July 1, 2020.

So what are the key changes to the Divorce Act as of July 1, 2020?

The key issues this article will discuss touch on the following issues:

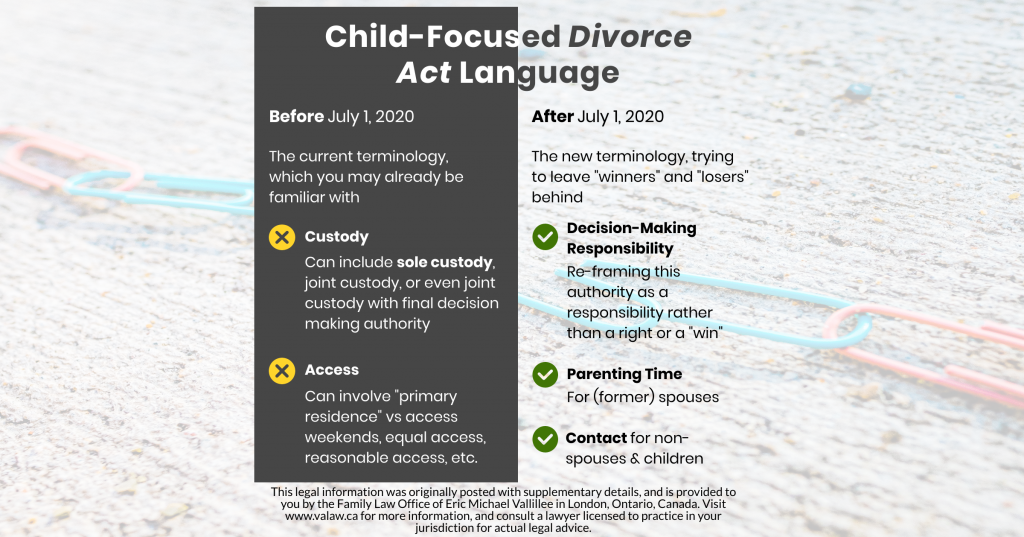

- Using more child-focused and less inflammatory language in family law cases

- Relocation of a child

- Increasing focus on the best interests of children

- Attempting to give more consideration to the issue of domestic violence/family violence

Child-Focused Language

One of the earliest and most emotionally challenging aspects of family court cases can be the experience of being served with court papers by your ex that tell you they are asking the court to grant them “sole custody” of your children. It can feel like your ex is trying to take your kids away from you, or like they are asking the court to declare that you’re not really a full parent of the kids anymore. This is often an unavoidable effect of the way the law is currently written.

The effect that those two words, “sole custody”, can have on the tone of the court proceedings and the approach of both parents right from the get-go can be staggeringly harmful. It can drive parents to fight each other, see each other as bitter enemies, and to try to prove they are the “good parent” and the other party is the “bad parent”. Most family law professionals, as well as the courts and the government want to move away from that to avoid unnecessary, years-long “custody battles” that ultimately harm relationships, hurt kids, and end up costing both parents a lot of money.

To try to shift the focus in family court away from “winners” and “losers”, the changes to the Divorce Act will see a new focus on “parenting arrangements” and “decision-making” responsibility rather than “custody” and “access”. Here’s a quick summary of how that will look in practice:

As is currently the case, decision-making responsibility will be able to be granted to one or both spouses after July.

Relocation of a Child

Currently, parents are already not generally permitted to move a child away from the other parent in the vast majority of circumstances, even if they are “just an access parent” without the other parent’s consent or a court order. As of July 1, 2020, the Divorce Act will contain a new framework that spells out in more detail precisely what should happen when one parent wants to move if the move is likely to have a significant impact on the child’s legally-protected relationships.

At least 60 days before the proposed move, the parent proposing the move will be required to provide written notice in a specific form to the other parent which includes:

- The proposed date of the proposed move;

- The new address and contact information for the moving parent and child as a result of the move;

- A proposal for a new parenting arrangement that includes “how parenting time, decision-making responsibility or contact, as the case may be, could be exercised”.

The other parent (or person with a contact order) will then have the chance to object in writing if they wish to do so, and if the parties do not come to an agreement, either of them may then bring an application (or motion to change, as applicable) to ask the court to decide the issue of mobility.

This new framework may look somewhat familiar to some parents as it is very similar to standard clauses that family lawyers in Ontario often negotiate or ask a court to impose already, but as of July, 2020, it will be the standard imposed by law for married and divorced couples whether it’s included in a court order, settlement, or separation agreement, or not, across Canada.

Another interesting change however, that is also quite different from the standard approach today, is that the court will be prohibited from considering whether a parent who is asking permission to relocate would relocate without the child anyway if the court refused permission to bring the child with them. The Department of Justice explains the reasoning for this change as follows:

“Parents seeking to relocate with their children are sometimes required to answer in court the difficult question of whether or not they would proceed with a relocation if they were not permitted to bring their children. A response of ‘I won’t relocate without my child’ may be interpreted as evidence that the proposed relocation is not sufficiently important and should not be permitted. A response of “I would relocate without my child” may be interpreted as evidence that the parent is not sufficiently devoted to the child.

This provision would prohibit courts from considering this question – or the parent’s response – if raised in the context of the court proceedings. This will assist in focusing on the specific legal issue before the court.”

Further Increase in Focus on Best Interests of Children

Currently, section 16(8) of the Divorce Act requires that a court making an order about custody of a child under the Act “shall take into consideration only the best interests of the child of the marriage as determined by reference to the condition, means, needs and other circumstances of the child”. In other words, it’s already supposed to be about what’s best for the kids, not what’s best for the parents.

As of July 1, 2020, the law will go further and specifically require the courts to consider the following factors:

- A child’s needs, given their age and stage of development, such as the need for stability;

- The child’s relationship with each parent;

- Relationships with siblings, grandparents, and other important people in the child’s life;

- Care arrangements before the separation, and what the future plans are for the care of the child;

- The child’s own views and preferences;

- Cultural, linguistic, religious and spiritual upbringing and heritage, including Indigenous upbringing and heritage;

The court will also have to consider each Parents’ ability and willingness to:

- Care for the child;

- Support the child’s relationship with the other parent; and

- Cooperate and communicate with the other parent about parenting issues.

Any family violence, existing criminal or civil court order, and other legal measures already in place will also have to be considered (as they generally are now) along with the impact the violence has on the appropriateness of making an order that would require people who were involved to cooperate on issues affecting the child.

The courts will also still be able to consider any other factor that has an impact on the child’s circumstances and best interests, but these factors will have to be considered in every case as a basic set of criteria.

Family Violence/Domestic Violence

Domestic violence or family violence was not previously directly addressed by the Divorce Act itself, leaving gaps in the way courts have dealt with the issue between the various provinces, in cases where litigants are married or former spouses. With the changes coming into force on July 1, 2020, courts across the county will be required to take any instances of family violence or domestic violence involving the parties or the children into account.

Family violence will be defined as “any conduct, whether or not the conduct constitutes a criminal offence, by a family member towards another family member, that is violent or threatening or that constitutes a pattern of coercive and controlling behaviour or that causes that other family member to fear for their own safety or for that of another person — and in the case of a child, the direct or indirect exposure to such conduct — and includes

- physical abuse, including forced confinement but excluding the use of reasonable force to protect themselves or another person;

- sexual abuse;

- threats to kill or cause bodily harm to any person;

- harassment, including stalking;

- the failure to provide the necessaries of life;

- psychological abuse;

- financial abuse;

- threats to kill or harm an animal or damage property; and

- the killing or harming of an animal or the damaging of property.

If family violence is found to be a factor in a particular case, the court will be required to consider whether there is a pattern of “coercive and controlling behaviour”, whether a child involved in the proceedings has been the subject of family violence or indirectly exposed to it, and any risk of physical/psychological/emotional harm to a child.

The court will also be required to consider any steps taken by the person “engaging in” the family violence to prevent further violence from occurring and to better care for the children in their family. In other words, if a parent who as acted in an abusive manner enrolls in counselling, seeks psychological help, can demonstrate that they are working to improve themselves, and improve their parenting ability, that will be something the court needs to take into account as well when making decisions about children in a divorce proceeding.

Of course, there are many other changes coming in July, and this article is just intended to highlight some of the key shifts that are coming our way this summer. If you need more information about divorce, custody, access, separation, or family law in London, Ontario, call the Family Law Office of Eric Michael Vallillee at 519-488-5263 or toll-free at 1-866-428-1063.